Venturing to describe the Carolina Theatre when it opened in 1927, a Charlotte journalist declared, “It is alive, and the audience itself is a part of the alluring picture.” The belief that theatergoers could be transported to an exotic locale, and feel like active participants in a fantasy world, rather than passive, aloof observers, was a defining feature of the atmospheric theaters that became popular in the United States during the 1920s. Architects designed atmospherics like the Carolina—sometimes called “stars-and-clouds” theaters—to create the feeling of watching a film outside, under a starry sky, in such fanciful and enchanting settings as Italian gardens, open-air Persian courtyards and Spanish patios.

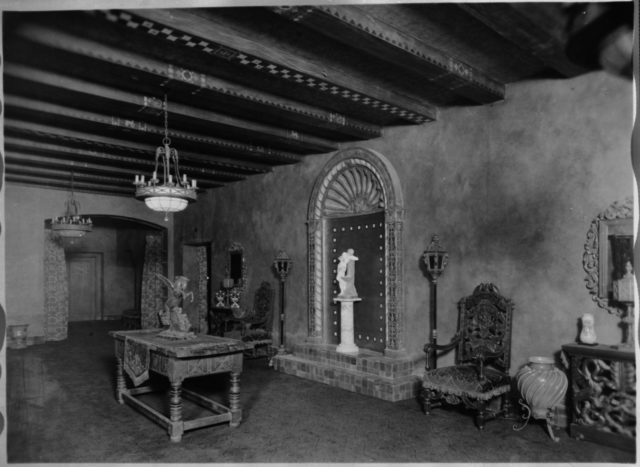

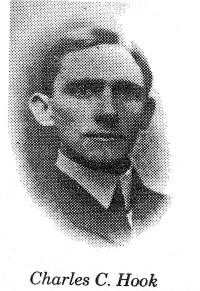

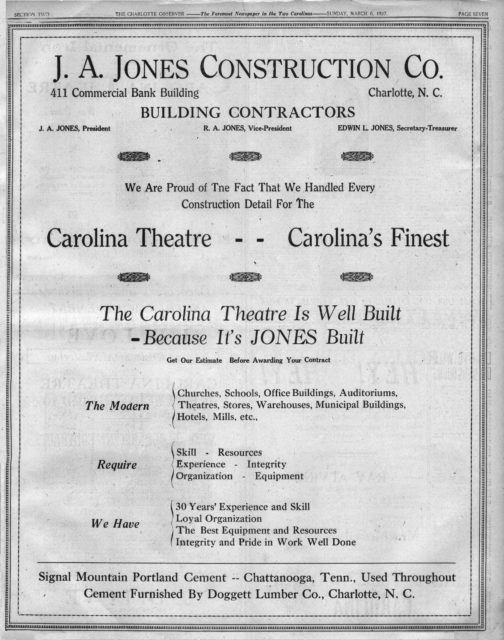

In this vein, the original Carolina Theatre, created by Charlotte architect C. C. Hook and New York theater designer R. E. Hall, drew moviegoers into a richly drawn, make-believe world, blending elements of European décor to suggest an exotic—and above all, regal—environment. The theater’s eclectic exterior, replete with a wrought iron ticket booth and decorative tile roof, hinted at the marvels to be found inside. As described by the Charlotte Observer, the main lobby was imitative of a grand outdoor patio, surrounded by “picturesque facades of old world palaces, colonnades of graceful arches, romantic balconies, the tower of ancient castles and the mystical beauty of an old Spanish cathedral window.”

From these rich surroundings, audiences entered the theater itself, where they could gaze up into “the deep blue of the Mediterranean sky, with an occasional twinkle of a far-off star, and the restful tranquility of fleecy clouds slowly drifting by,” and admire the graceful white pigeons and brightly-colored parrots that were “perched here and there.” Climbing vines, tropical foliage, a bounty of flower arrangements and a proud peacock, surveying his surroundings from atop a high balcony, completed the illusion.

It is little wonder that a pioneer of the early motion picture industry famously declared, “We sell tickets to theaters, not movies.”

Sources:

Richard Koszarski. An Evening’s Entertainment: The Age of the Silent Feature Picture, 1915-1928. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1990.

Ben M. Hall. The Best Remaining Seats: The Golden Age of the Movie Palace. New York: De Capo Press, 1988.

David Naylor. American Picture Palaces: The Architecture of Fantasy. New York: Prentice Hall Press, 1981.

“Carolina Theater Places Charlotte in High Class As Amusement House Center,” Charlotte Observer, March 6, 1927.

When it opened in 1927, the Carolina Theatre boasted a “Mighty Wurlitzer” organ. Thousands of these gigantic pipe organs were installed in theaters throughout the United States to accompany silent movies in the early 1900s. Designed by British inventor Robert Hope-Jones, theater organs could imitate the different instruments of an orchestra—from piano, flute, and violin to trumpet, drums, and cymbals—and create special sound effects, from train and boat whistles, car horns and bird whistles, to crashing thunder and pouring rain. The so-called “silent” movies were anything but noiseless, as audiences were absorbed in an extravaganza of sound and music.

When it opened in 1927, the Carolina Theatre boasted a “Mighty Wurlitzer” organ. Thousands of these gigantic pipe organs were installed in theaters throughout the United States to accompany silent movies in the early 1900s. Designed by British inventor Robert Hope-Jones, theater organs could imitate the different instruments of an orchestra—from piano, flute, and violin to trumpet, drums, and cymbals—and create special sound effects, from train and boat whistles, car horns and bird whistles, to crashing thunder and pouring rain. The so-called “silent” movies were anything but noiseless, as audiences were absorbed in an extravaganza of sound and music. Norris played a variety of music on the theater’s Wurlitzer organ, including classic tunes and ballads as well as popular hits of the day, interspersed with engaging commentary about current and coming cinema attractions. The popular concerts made Norris a well-known personality in Charlotte. The Mecklenburg Times reported that he “quite captivated Charlotte radio fans with his sympathetic interpretations of their favorite musical numbers,” and staff members of the radio station joked that Norris might need to “engage the services of a secretary” to handle his fan mail.

Norris played a variety of music on the theater’s Wurlitzer organ, including classic tunes and ballads as well as popular hits of the day, interspersed with engaging commentary about current and coming cinema attractions. The popular concerts made Norris a well-known personality in Charlotte. The Mecklenburg Times reported that he “quite captivated Charlotte radio fans with his sympathetic interpretations of their favorite musical numbers,” and staff members of the radio station joked that Norris might need to “engage the services of a secretary” to handle his fan mail. When The Sound of Music, starring Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer, opened with a gala premiere at the Carolina in March of 1965, local advertisements boasted that the theater was just one of twenty five in the country—and the only movie house in the Carolinas—where the movie was being shown. A film adaptation of a Broadway musical, The Sound of Music was based on the true-life story of the Von Trapp Family Singers in Austria on the eve of World War II.

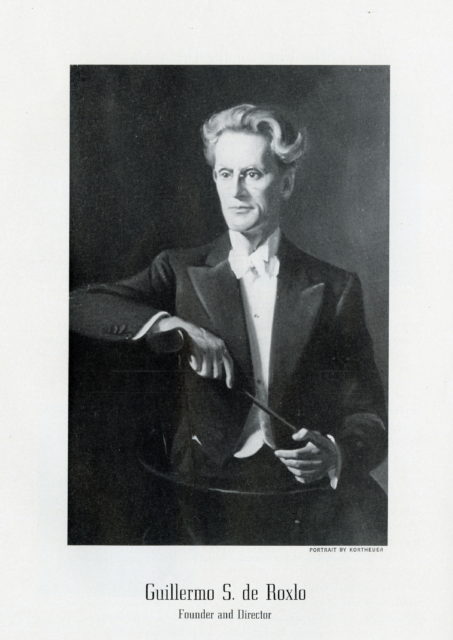

When The Sound of Music, starring Julie Andrews and Christopher Plummer, opened with a gala premiere at the Carolina in March of 1965, local advertisements boasted that the theater was just one of twenty five in the country—and the only movie house in the Carolinas—where the movie was being shown. A film adaptation of a Broadway musical, The Sound of Music was based on the true-life story of the Von Trapp Family Singers in Austria on the eve of World War II. Members of the fledgling Charlotte Symphony Orchestra had been practicing together for just three months when they took the stage for a debut performance at the Carolina Theatre on the evening of March 20, 1932. The night’s feature presentation was the premiere of a symphony written by Spanish composer and violinist Guillermo de Roxlo, who also served as conductor for the concert. de Roxlo began composing the symphony in 1931 while living in Cuba and completed the work upon arriving in Charlotte. As described by a local journalist, the work’s three movements, “splendidly interpreted” by the musicians, carried listeners through “the many great emotions of a human being.”

Members of the fledgling Charlotte Symphony Orchestra had been practicing together for just three months when they took the stage for a debut performance at the Carolina Theatre on the evening of March 20, 1932. The night’s feature presentation was the premiere of a symphony written by Spanish composer and violinist Guillermo de Roxlo, who also served as conductor for the concert. de Roxlo began composing the symphony in 1931 while living in Cuba and completed the work upon arriving in Charlotte. As described by a local journalist, the work’s three movements, “splendidly interpreted” by the musicians, carried listeners through “the many great emotions of a human being.”

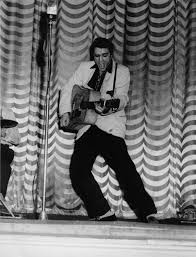

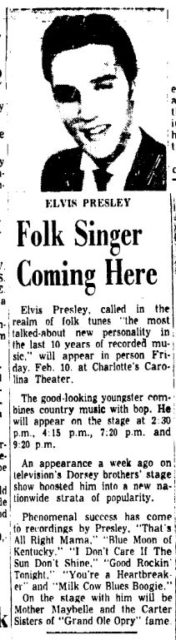

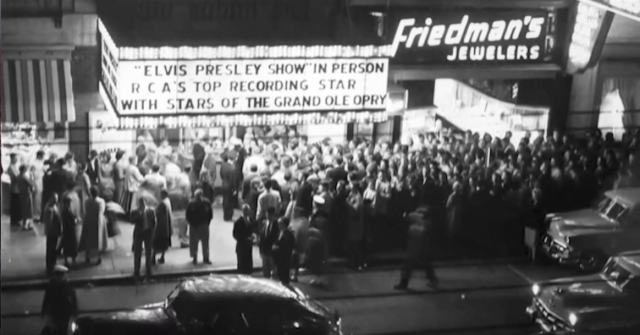

When Elvis Presley stepped onto the stage at the Carolina Theatre in February 1956, he was only 21 years old and just emerging as a national phenomenon, propelled by extensive touring, appearances on national television and the recent release by RCA Records of the hit song, “Heartbreak Hotel.”

When Elvis Presley stepped onto the stage at the Carolina Theatre in February 1956, he was only 21 years old and just emerging as a national phenomenon, propelled by extensive touring, appearances on national television and the recent release by RCA Records of the hit song, “Heartbreak Hotel.”

In preparation for the big event, a “Gone With the Wind” ball was held at the Charlotte Hotel, and a local woman was crowned as the city’s own “Scarlett O’Hara.” The following day, Charlotte’s “Scarlett” visited local businesses on a “thrilling Shopping Tour of Charlotte stores,” as billed by the Charlotte Observer. Chauffeured in a late-model Ford Mercury provided for the occasion by a local car dealer, “Scarlett” made stops at clothing stores, a dry cleaner and a candy shop featuring “Scarlett Chocolate,” among other Charlotte retailers.

In preparation for the big event, a “Gone With the Wind” ball was held at the Charlotte Hotel, and a local woman was crowned as the city’s own “Scarlett O’Hara.” The following day, Charlotte’s “Scarlett” visited local businesses on a “thrilling Shopping Tour of Charlotte stores,” as billed by the Charlotte Observer. Chauffeured in a late-model Ford Mercury provided for the occasion by a local car dealer, “Scarlett” made stops at clothing stores, a dry cleaner and a candy shop featuring “Scarlett Chocolate,” among other Charlotte retailers. Stage actress Ethel Barrymore garnered high praise for her performance as an English schoolteacher, struggling against ignorance and indifference in a remote Welsh village. Written by British dramatist Emlyn Williams, The Corn is Green had a two-year run in London before wartime bombing forced the closing of playhouses. After coming to the United States, it quickly became a Broadway hit and earned numerous awards, including the New York Drama Critics’ Circle award for best foreign play of the year.

Stage actress Ethel Barrymore garnered high praise for her performance as an English schoolteacher, struggling against ignorance and indifference in a remote Welsh village. Written by British dramatist Emlyn Williams, The Corn is Green had a two-year run in London before wartime bombing forced the closing of playhouses. After coming to the United States, it quickly became a Broadway hit and earned numerous awards, including the New York Drama Critics’ Circle award for best foreign play of the year.

Chicago native Sam Katz was president of the Publix Theatres Corporation (later Paramount Publix Corporation) and the driving force behind the company’s explosive growth. To Katz, the purpose of a well-run theater went far beyond entertainment in its value to the public. He declared, “A properly conducted theater is of the same importance to a community as a school or church. Such a theater contributes to the general welfare of the community, because wholesome recreation is essential to its well-being.”

Chicago native Sam Katz was president of the Publix Theatres Corporation (later Paramount Publix Corporation) and the driving force behind the company’s explosive growth. To Katz, the purpose of a well-run theater went far beyond entertainment in its value to the public. He declared, “A properly conducted theater is of the same importance to a community as a school or church. Such a theater contributes to the general welfare of the community, because wholesome recreation is essential to its well-being.”

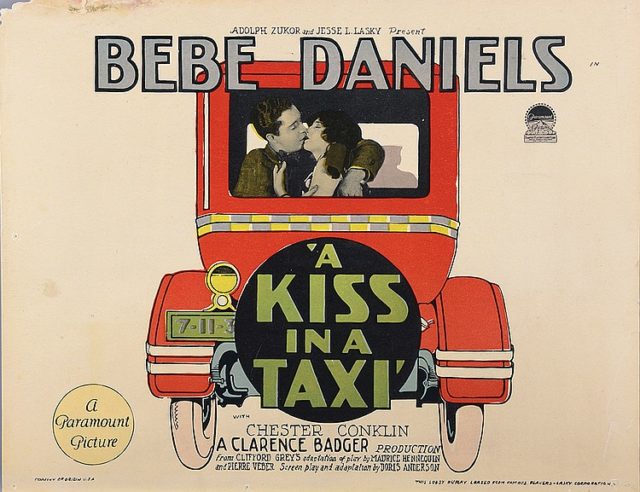

1920s: In the spring of 1927, local high school student Henry S. Cowell became an usher at the newly-opened Carolina Theatre, a job he loved.

1920s: In the spring of 1927, local high school student Henry S. Cowell became an usher at the newly-opened Carolina Theatre, a job he loved.